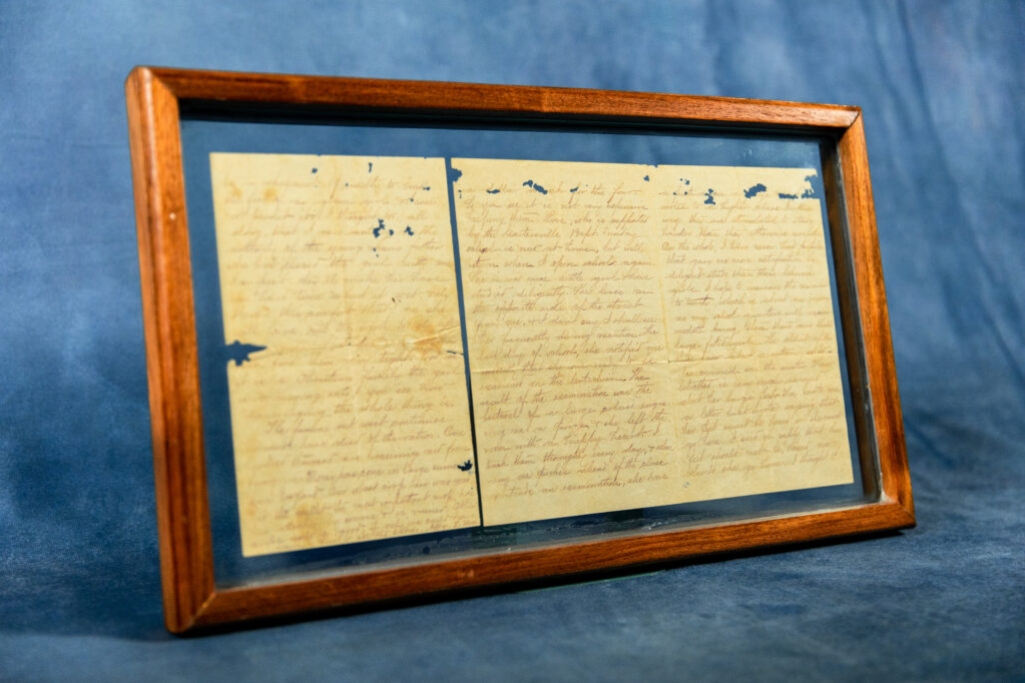

Earlier this month, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary (SEBTS) received the donation of an occasional letter written by Lottie Moon — lifelong missionary to China in whose memory Southern Baptists receive their annual Christmas offering for international missions.

In 2007, Keith Harper, senior professor of Baptist studies at SEBTS and editor of “Send the Light: Lottie Moon’s Letters and Other Writings” acquired the historic letter from a Civil War collector in the metro Atlanta area.

“The letter was discovered tucked away in the middle of a packet of Civil War letters,” Harper recalled, amazed to find the letter so well preserved.

Curious about the authenticity of the letter, Harper pursued a few lines of enquiry. What finally confirmed its authenticity for him was Moon’s script and idiosyncratic signature with periods after her first initial and after her last name. Harper made a bid and purchased the letter — honored to own an artifact documenting Baptist missions in China. Now 16 years later, Harper and his wife have decided to donate the letter to the SEBTS archives to preserve its history for future generations.

“Southeastern is a Great Commission seminary, and I thought, what better place for that letter to be than here at Southeastern,” shared Harper. “We hoped it would be part of the focal point of who we are as an institution. When my wife and I thought of it that way, we both decided we should donate it to Southeastern.”

“We make this donation for the next generation and for the generations after them,” added Harper. “Artifacts, like the letter, are tangible links to the past. It is a link not only to Lottie Moon but also to her time and her world. The letter is tangible evidence that she truly gave herself to the missionary endeavor.”

We make this donation for the next generation and for the generations after them.

An occasional letter from Moon’s fifth year in Tengchow, the letter was written in correspondence with a Mrs. Wilkes, and in it, Moon applies the gospel to the Chinese custom of foot-binding — the agonizing process by which girls would have their toes broken and feet deformed over time into a crescent-shaped shoe.

After updating Mrs. Wilkes on the state of her ministry and boarding school in the region, Moon shares at length about an incident surrounding one of the young women at her boarding school — a 17-year-old “large-footed girl” who was betrothed to be married into a Christian family later that year. Upon her arrival at boarding school, the girl had unbound her feet under Moon’s care.

Threatened by the girl’s betrothed, Moon advocated for the girl and refused to subject her to that suffering. Although the girl’s future father-in-law had previously made concessions, he had since reneged on that understanding and showed up one day to confront Moon. However, Moon would not let him argue his case or force the girl to suffer such cruelty.

Moon’s concern was not that Chinese cultural practices differed from those she remembered from her childhood in the West. Instead, her concern was that foot-binding was not consistent with the gospel. Moon confronted the young man’s father and with great conviction told him that foot-binding was “utterly inconsistent with the gospel of Jesus.”

Moon was resolute, so the father backed down. As she writes in her letter, “I carried my point. I was determined that no such suffering should be inflicted [on] a girl under my roof and that I would not be a witness of such suffering. He backed down completely.”

As Moon recounts later in the letter, she vowed to fight this cruel custom all her life. For Moon, the suffering imposed on young women was inconsistent with the reality of God’s redeeming love in Christ and the radical neighbor love and spiritual priorities that should characterize the Christian’s changed life. What was consistent with the gospel of Jesus, however, was Moon’s self-giving care for the girls under her charge and for the people in her region whom she had pursued with the gospel, surrendering her familiar life in the West to the call of Christ in the East.

As attested by the letter, even in her early years of ministry, Moon had a deep love for the Chinese people and an unwavering commitment to the gospel’s power to transform human hearts and cruel cultural practices. For Harper, the letter is also a remarkable example of her disciplined letter writing, which she stewarded as a way to challenge others to support or join her missionary efforts.

“Lottie Moon had what would be considered today a master’s degree in English,” recounted Harper. “Her letters were articulate and well-composed. When people would read her letters, it was often many people’s first glimpse into an international culture. She took people from Alabama, Georgia, and the rural South and transported them through her letters to a different continent and, in many ways, to a different world.”

“Not only would she say, ‘This is the world I live in,’ but also she would invite people to join her: ‘Will you help me in this enterprise? Will you surrender your life? Will you send us funds? Will you participate?’” recounted Harper. “She was one of many international missionaries who would call others to participate in their cross-cultural efforts. Even at a time when women’s opportunities were often limited in society, she challenged women to serve by telling them that they too could do missions.”

Even at a time when women’s opportunities were often limited in society, she challenged women to serve by telling them that they too could do missions.

As a life-long Baptist missionary, Moon was committed to the task of fulfilling the Great Commission among the unreached and least reached. As a 4-foot-3-inch single woman, Moon courageously went where many others did not dare to go because she believed what was on God’s heart should be on her heart as well. Her legacy of faithful ministry not only has inspired generations of Baptist women and men to join in the mission but also stands as a testament to Jesus’s abiding presence and amazing power in the life of those who go make disciples.

The letter and its transcription can be viewed online on the SEBTS archives.