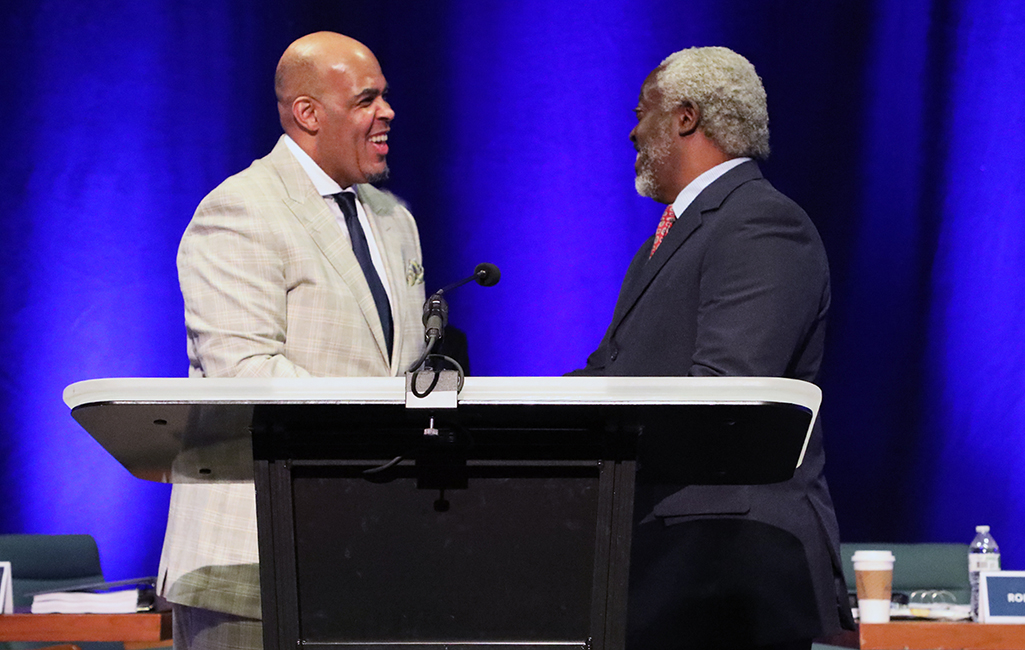

Rolland Slade, senior pastor of Meridian Baptist Church in El Cajon, Calif., concludes the 2012 Opening Day ceremonies with a prayer as administrator for California Little League District 66. Slade has served as administrator since 2004.

EL CAJON, Calif. (BP) — Rolland Slade loves youth baseball. It’s been a part of his life for 25 years as a parent, coach and administrator for Little League Baseball and Softball. He’s seen how it bonds communities and gives young people a place to grow.

As a pastor, he’s been a spiritual lifeline for many through it. He’s conducted funerals, weddings and vow renewals, a few times at home plate.

With anything positive, though, some negative will creep in.

Slade has also witnessed the ugliness that can come when a parent thinks incompetent coaches and know-nothing umpires are the only thing standing between their son and the big leagues. He’s heard from those who aren’t shy about sharing their opinions from the stands.

Fan behavior in youth sports is driving a shortage of officials, but also volunteers, said Slade, who has served the last 19 years as an administrator for Little League.

“I’m a volunteer like everyone else. My responsibilities are to lead a district with 10 leagues, to help them administer and interpret rules that come down from Little League International,” he told Baptist Press.

“We’re struggling to find volunteers. We came out of COVID, and were building up in some cases, but receding in others. Most people want to sign up their kids to play, but then step back, not wanting to coach or umpire.”

Money is certainly a factor. In Fall 2022 the average family spent $883 on one child’s primary sport per season, according to The Aspen Institute. That’s down slightly from $935, pre-pandemic. Even so, U.S. families spend $30-$40 billion annually on children’s sports activities, more than the annual revenues of any professional league.

Travel ball costs include coaches, equipment, team insurance and tournament fees, which include officials for those locales. There is also hotels, food on the road and all the other costs associated with travel.

That kind of investment drives a certain expectation from the investor (parent). And when those benefits don’t materialize, officials are often the scapegoat.

For the record, Little League umpires aren’t compensated, unless you count a burger and drink from the concession stand.

A report issued by the National Association of Sports Officials last year estimated that 30 percent of officials have not returned to youth sports since the pandemic. Of those, up to 25 percent are never expected to come back.

It leads to a cycle of less-experienced referees and officials being placed on the field, who will make mistakes, which lead to more fan outbursts.

“It’s past the tipping point. We’ve tipped. Now where do we go from here?” asked a veteran high school football referee in Maryland.

It’s becoming more common for stadium lights typically ablaze on Friday nights to move to Thursday and even Saturday out of necessity for lack of officials. In August, a member of the San Diego County Football Officials Association pleaded with fans to behave.

“I never thought our numbers [of officials] would decrease by about half,” Gary Gittelson told CBS8 News.

Stories can be found of officials being attacked by fans. Slade never experienced that, but he has had his share of tense situations.

One involved a game that went into extra innings. The losing team interpreted a rule differently. The team, coaches and parents focused their ire on Slade and officials.

“It can get intense, but I want to maintain my testimony,” he said. “People know what I do for a living, so if I get upset, I know to walk away, to be cool and calm and thank the Lord for the opportunity because I’m representing Him.”

A bill to be voted on April 14 by the Texas House of Representatives shows that governments are taking note.

House Bill 2484 would prohibit a spectator of a University Interscholastic League game from attending any future UIL events if they “intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly” cause bodily harm to an official during an extracurricular activity. If it passes, the bill could take effect Sept. 1.

When his kids played Little League, Slade would sit with other parents. A time or two he was asked to sit somewhere else, because no one wanted to cuss in front of a preacher.

The option of “Don’t cuss at a kids’ baseball game” apparently wasn’t considered.

“I’ve known folks who were professing believers acting out at games,” Slade said. “Christians need to know that they can’t put their faith on hold because they’re at a sporting event. They’re still a child of God.

“Even if they don’t feel like representing the Lord, they do.”

It’s happened when, during a pause in a game because a fan is being warned, Slade will talk to a player to learn the fan is that child’s parent. “You find out they’re embarrassed by that,” he said.

Not long ago, a fan became incensed over one of Slade’s calls. He attempted to demean Slade and even question his character. The feedback wasn’t helpful, but it was relentless.

The call happened in an instructional league game for 6- and 7-year-olds.

Dealing with players is more understandable. Slade once threw a catcher out of a game who kept talking back. The final straw was the expletive uttered in Slade’s direction on a called third strike while batting.

Slade found the player afterwards at the snack bar and talked it through, explaining how he didn’t want the youngster to lose out on future tournaments because of one bad moment.

“His response was ‘Really?’ and he went on to have a great season, made All-Stars,” said Slade. “On the day of that announcement he came over to me and shook my hand and said, ‘Thank you, Mr. Rolland. I really appreciate it because if you had written me up, there’s no way I’d be doing this.’

“He went on to be an outstanding catcher, and, I think, became All-League in high school. He’s a firefighter now.”

Slade hopes Christians see the impact they can have both in the stands and on the field. There are opportunities available.

“You can be there and live out your faith,” he said. “Get to know families. It’s an opportunity to touch lives.”

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Scott Barkley is national correspondent for Baptist Press.)