As a child growing up in Virginia, Marshal Ausberry never understood it. Why were monuments to Confederate soldiers prominently displayed in public spaces across his state?

“To see the Confederate flag and these larger than life statues to over-romanticized Confederate heroes of the Confederate South strewn throughout Virginia constantly reminded me that there were people who were willing to fight, bleed, sacrifice and die to keep black people chained into a system of brutality and bondage,” said Ausberry, who pastors Antioch Baptist Church in Fairfax Station, Va., and is first vice president of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC).

Nearly two weeks after a black man, George Floyd, died in police custody – after a white police officer used a knee to pin his neck to the ground for several minutes – many of those monuments are coming down. On June 4, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee astride a horse would be removed from a 40-foot-tall granite pedestal near downtown Richmond.

It’s only one of several in a string of Confederate icons being removed from public view nationwide. Some were illegally defaced or toppled by rioters protesting Floyd’s death.

Ausberry, who is president of the National African American Fellowship of the SBC, said removal of the Lee statue was “130 years overdue.” Several other prominent Southern Baptist leaders expressed similar sentiment.

Steve Gaines, pastor of Bellevue Baptist Church in Cordova, Tenn., and a former SBC president, was among a dozen Memphis-area Southern Baptist pastors who joined others in 2017 to advocate for the removal of a statue honoring Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Gaines, who was serving as SBC president at the time, said Friday such monuments are a hindrance to Christian love and unity.

“I just don’t see any need for us to have a stumbling block over a war that in my opinion, the South was not on the right side of that war,” Gaines told Baptist Press. “It was holding and oppressing millions of African Americans that should have never been forced to be slaves, and obviously today their descendants are offended by it.

“Why in the world as a Christian would I want to set any kind of stumbling block before my brother?”

In 2016 under the presidency of Ronnie Floyd, messengers at the SBC Annual Meeting passed a resolution encouraging Christians to “exercise sensitivity” and “to discontinue the display of the Confederate battle flag as a sign of solidarity of the whole Body of Christ, including our African American brothers and sisters.” A key amendment was offered by former SBC president James Merritt, and the resolution noted Floyd’s call for Southern Baptists to “rise up and cry out against racism that still exists in our nations and our churches” and to “replace these evils with the beauty of grace and love.”

Floyd, who is now president and CEO of the SBC Executive Committee, said Friday “every town, city and state in the nation will wrestle with” how to handle Confederate monuments.

“Whatever is decided in Virginia or elsewhere, the most important decisions each day will be the decisions that will be made about the kind of future we desire to experience together,” Floyd said. “This will ultimately be determined by one thing: the way we honor one another, treat one another, and respond to another regardless of the color of our skin.

“This will show the kind of America we will become in the future. This generation of Americans need to ensure that future generations of Americans live in a nation where ‘We the people’ means all the people – regardless of the color of their skin.”

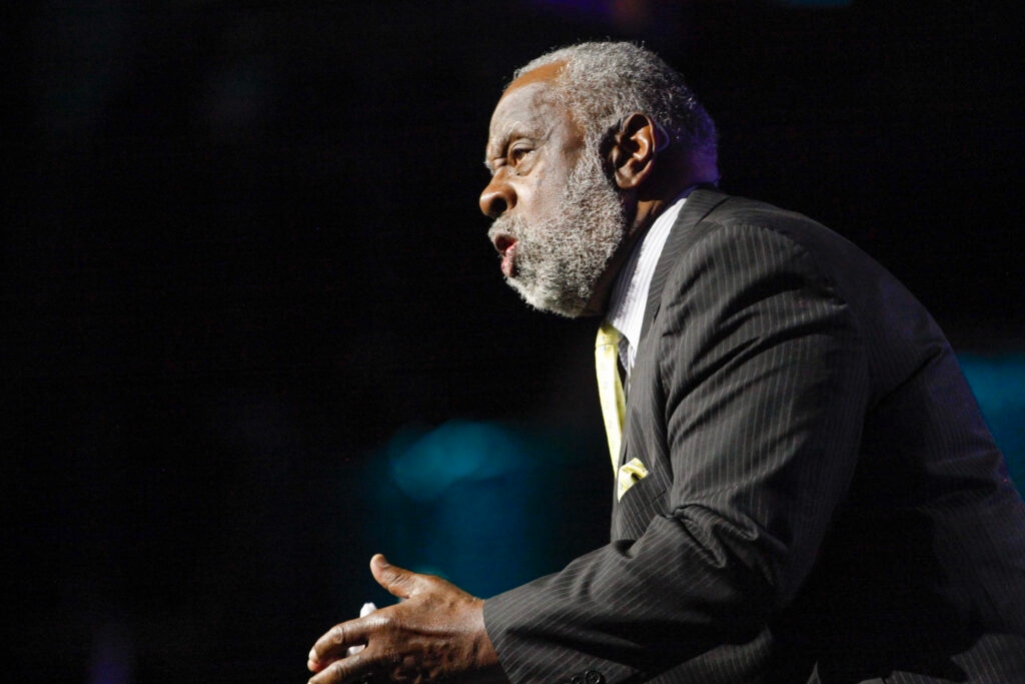

Former SBC President Fred Luter, who from 2012-14 served as the first African American president of the SBC, was among an ecumenical group of pastors who successfully supported the removal of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans between 2015 and 2017. There, the climate was so controversial, three of the monuments had to be removed at night.

“I supported the removal of the monuments because the monuments were causing racial tension in the city,” said Luter, pastor of Franklin Avenue Baptist Church in New Orleans. “The monuments were a constant reminder of a very segregated time in the life of our country. Taking the monuments down benefited race relations in New Orleans.

“The monuments promoted racism and division against those in the African American community. There was never anything positive that these monuments represented. They separated us rather than bringing us together.”

In Virginia, Northam’s decision to remove the statue of Lee from its prominent place on Richmond’s Monument Avenue followed Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney’s plan to remove four other Confederate statues from the avenue, the Associated Press reported. Beginning July 1, changes to Virginia law will allow cities to decide for themselves whether Confederate monuments in their jurisdictions will be removed.

In recent days, monuments have been removed, or plans have been made to remove them, in several other cities nationwide. The actions are reminiscent of a wave of removals of Confederate statues and monuments that occurred after the 2015 murders by a white man of nine blacks at a Bible study and prayer meeting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. The current wave has been spurred by protests that have sprouted across the nation since George’s death on Memorial Day.

“In one sense,” Ausberry said, “it’s almost as if we are only beginning to close out the Civil War, which ended with General Lee’s surrender to General Grant in Appomattox in 1865, some 155 years ago. I know it will be hard for some to see these statues removed from full public display.

“Regrettably, they represent a part of American history not to be hidden, but to be displayed in a more appropriate and respectful manner for all parties involved.”

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Diana Chandler is Baptist Press’ general assignment writer/editor.)