NASHVILLE (BP) – Thomas Jefferson Bowen was the first Southern Baptist missionary to focus on winning Muslims to Christ and the first missionary sent by the convention to Central or South America, but generations have not known his name.

By 1860, Southern Baptists had only pioneered mission work in four countries, and Bowen was responsible for two of them. He was a national hero, publishing with the Smithsonian Institution, testifying in Congress, preaching and speaking throughout the eastern U.S., yet mental illness all but erased the memory of his existence.

Jim Hardwicke, author of “Unthinkable: The Triumph and Endurance of Forgotten American Hero T.J. Bowen,” spent years digging up Bowen’s story, consulting more than 1,000 primary sources, so that future generations can be inspired by his example.

Born in the Georgia frontier of 1814, Bowen joined the fight to defend the Republic of Texas as one of the original Texas Rangers. Saved in 1840, he preached and helped establish churches and associations in southern Georgia, eastern Alabama and northern Florida.

“He was mainly preaching to blacks, the poor, the unreached–really the outcasts of society,” Hardwicke told Baptist Press. “He was usually very self-sacrificing. That was his nature. He would run toward danger, and he would run toward those who needed Christ.”

Around the time the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1845, Bowen read early reports of missions work and became burdened for Central Africa.

“Most of the Southern Baptist work had been on the coast in Liberia and West Africa,” Hardwicke said, and Bowen thought the work should proceed to the interior.

Bowen offered himself to the Foreign Mission Board as a missionary and was approved but had to raise his own funds. They sent with him another white man as well as a slave whose freedom Bowen helped purchase.

“It was a great adventure, very dangerous,” Hardwicke said. “Everybody knew it.”

At the time, most people who traveled from America to West Africa contracted tropical fevers as they attempted to acclimate, and many died early in their attempts at evangelization.

The trio pressed nearly 70 miles into the interior of Africa and preached briefly before the two white men got very sick, Hardwicke said. The former slave nursed them for a time but then returned to the coast. Soon, Bowen’s associate died, leaving him to evangelize the African interior alone.

At the time, Africans were enslaving and selling other Africans. Bowen used his military experience to lead a city of 60,000 people to stand against the slave traders. In turn, the city leaders negotiated a treaty with the British to open the interior to white people.

“Evidently, through helping to negotiate the terms of this treaty, he played a key role in opening up Central Africa not only for himself, but for future missionaries,” Hardwicke wrote.

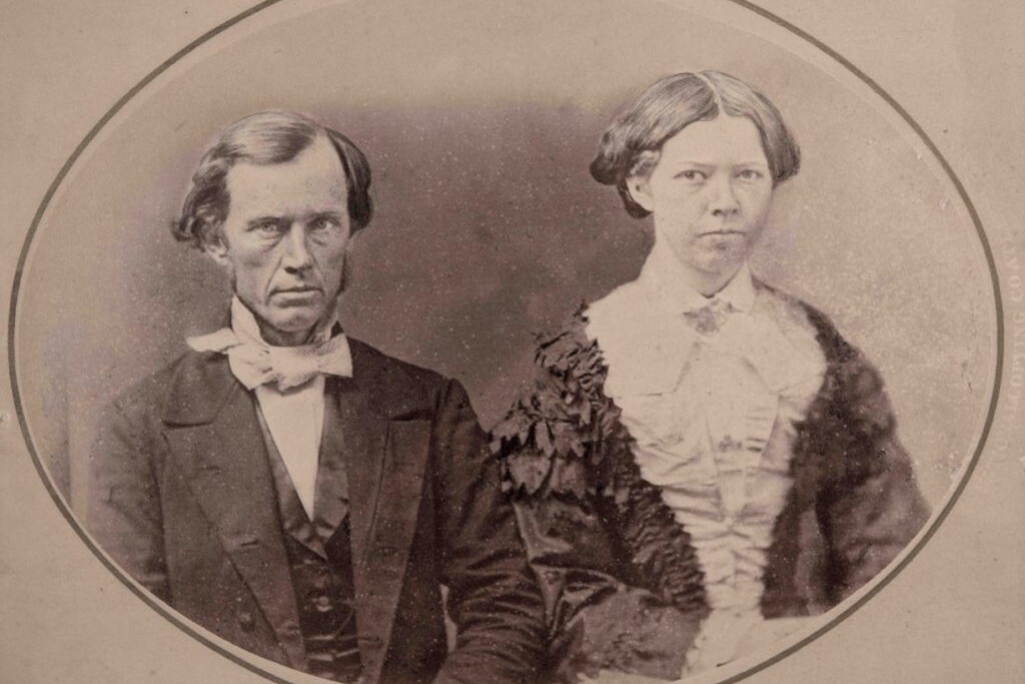

In 1853, Bowen returned to America where he would preach at the Southern Baptist Convention in Baltimore and marry a wealthy Georgian before returning for his second attempt at evangelizing the heart of Africa.

Southern Baptists at the time read about Bowen’s exploits in their denominational journals alongside those of the British missionary explorer David Livingstone, his contemporary.

The Bowens established the first Baptist mission station in Central Africa “against all odds,” Hardwicke said, and they had a daughter who lived only a few months. They continued to labor among Muslims and saw some converts in modern day Nigeria before severe health problems drove them back to the U.S. in 1856.

“All the diseases that killed most of the other white people left him physically and mentally maimed for the rest of his life,” Hardwicke said. “He started experiencing anxiety and depression in 1854. He began to be psychotic in 1854, suicidal in 1855.”

Despite his struggles, Bowen wrote “Central Africa,” a 359-page account of his explorations and missionary efforts, including the geography, people, animals and vegetation there. A prominent newspaper in Washington, D.C., called it “one of the most scientific ever written on an unknown country,” and it became a bestseller of its time.

Bowen also compiled a grammar and dictionary of the Yoruba language, and it was published by the Smithsonian Institution. As late as 1940, the grammar was still being used in Nigerian schools, and it was instrumental in translating the Bible into the Yoruba language, Hardwicke wrote.

That same Washington newspaper, The Daily National Intelligencer, assessed Bowen as surpassing Alexander the Great by noting “to penetrate alone into an extremely unknown and hostile region” without troops “is an achievement such as an Alexander never would have dreamed of undertaking.”

“It is comparative cowardice to be a conqueror shielded on all sides by an invincible army,” the newspaper wrote, according to Hardwicke’s book.

Bowen was in demand as a speaker throughout the SBC, and his testimony led the U.S. Senate to pass a bill calling for $25,000 to be spent exploring the Niger River with Bowen as the leader, but the idea failed in the House of Representatives.

Hardwicke wrote that Bowen’s “heroic courage and persuasive writing and speaking had captured his nation’s imagination of what could be done for Central Africa.”

While Bowen longed to return to Africa, his health kept him back. In 1859, the FMB agreed to send him the shorter distance to Brazil, where he planned to reach Yoruba slaves taken there from Africa.

Shortly after arriving with his wife in Brazil, Bowen ran afoul of the Roman Catholic authorities and was imprisoned on suspicion of inciting insurrection among the slaves. The FMB contacted the U.S. War Department, and the commander of the American fleet at Rio threatened to fire upon the city unless he was released, which he was.

“T.J. had experienced opposition in Africa, but nothing like he was experiencing in Brazil,” Hardwicke wrote.

Bowen suffered a major physical and mental breakdown in Brazil, and the Bowens returned home. Severe headaches and other ailments tormented him, and for the final 14 years of his life he wandered the South alone, without money and given to drunkenness.

Hardwicke asked two physicians to examine a primary document about Bowen’s health, and they determined the illnesses he acquired in Africa likely included malaria, Gambian sleeping sickness, worms and maybe even typhoid and strep.

“The parasites in his brain were seasonal,” Hardwicke said. “When they rode through their life cycles, he got worse physically and mentally.”

Bowen was in and out of an insane asylum in Georgia seven times, and that is where he died in 1875. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the asylum’s cemetery.

“[Southern Baptists] were embarrassed by his insanity, and they were embarrassed by reports of his drunkenness,” Hardwicke said. “So Southern Baptists wrote him off. They put a veil over his life, especially that part of his life. Because Southern Baptist historians ignored him, so did secular historians.”

In Nigeria, though, Bowen is still revered. He started what became the Nigerian Baptist Convention, and its website says it has grown to more than 20,000 churches with more than 10 million members. A university and a hospital there bear his name. From Nigeria, millions of people have been reached for Christ in other parts of Africa, Hardwicke noted.

A young man won to Christ by Bowen’s preaching in Florida followed in his footsteps to Brazil. It was that man, Richard Ratcliff, who spoke at an SBC annual meeting and persuaded messengers to send missionaries to Brazil, Hardwicke said, adding, “Now there are multiple millions of Brazilian Baptists.”

“I have no doubt that in heaven T.J. Bowen and Lurana are greatly honored,” Hardwicke said. “The fruit that has been born of their sacrifices is multiplied millions of believers and tens of thousands of churches in South America and Africa.”

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Erin Roach is a writer in Mobile, Ala.)