The Museum of the Bible has detailed the provenance and acquisition of the oldest known map of the constellations, a previously lost writing based on the notes from second century B.C. Greek astronomer Hipparchus’ “Star Catalogue.”

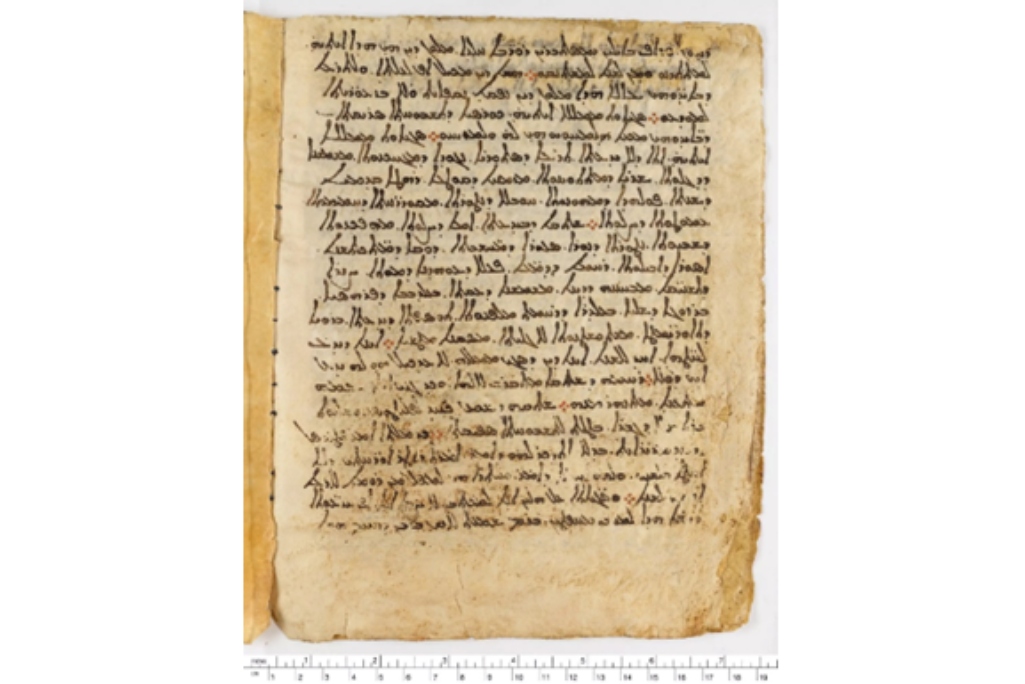

The notes had been written in the fifth century on vellum leaves that were recycled perhaps five or six centuries later to record the Christian manuscript “Codex Climaci Rescriptus” (Ladder of Divine Ascent) by John Climacus, the museum said in an Oct. 28 press release. An emerging process of multispectral imaging technology was used to reveal what was left of the older writings on the vellum, the museum said.

Bill Warren, a New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary expert in New Testament textual criticism, said the technology can make visible the faintest remnants of text that has been scraped away.

“Increasingly we’re using it and we’re actually finding several manuscripts that had another one written underneath,” Warren told Baptist Press (BP). “And it’s a pretty exciting time because every now and then, we’ll find one that’s a good biblical manuscript that was underneath. This time, it was on a Syriac manuscript.”

The older text was discovered by a team of scholars led by Peter Williams at Tyndale House at Cambridge University. Williams and Warren are among several scholars collaborating on the longstanding International Greek New Testament Project (IGNTP) to produce critical editions of the Greek New Testament. Williams is IGNTP president, and Warren is a member of the IGNTP committee of 26 scholars on the project that has the Museum of the Bible among its supporters.

In an ancient system of recycling vellum, a type of parchment made from calf skin, scribes would scrape away the existing ink, wash the vellum and use it for new writings. This is what occurred in the 10th or 11th century when a scribe at St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai needed vellum to record Climacus’ work. The scribe recycled leaves from an older manuscript, which evidently was a star map drawn in the fifth or sixth century and based on Hipparchus’ star catalogue.

While the star catalogue itself has little biblical significance, it does give greater insight into the astronomy conducted by the biblical magi referenced at the birth of Jesus, Warren told BP.

“The map itself has no biblical input, other than showing that they were very involved in mapping out the stars and such,” Warren said. “Now where that has implications on exegesis, which is different from the actual text, is the magi were actually ones who were involved in mapping out the stars. … This shows they’re part of a long line of studies in this area. There’s nothing quirky about them,” Warren said, clarifying that Christians would not, of course, use the stars to determine future events as did the magi. “They are part of a long history of trying to map out the stars.”

The technique of spectral imaging is important in the discovery of biblical text, Warren said.

“Sometimes our manuscripts contain old texts that we thought were totally lost, that are not biblical,” Warren said. “On the other hand, sometimes we find biblical text that would have been lost if we had not found them.”

Brian Hyland, the Museum of the Bible’s associate curator of medieval manuscripts, explained the work’s historical provenance to BP.

“This translation was most likely produced at St. Catherine’s Monastery by Mt. Sinai, where John (Climacus) had been the abbot in the early seventh century,” Hyland told BP. “This manuscript was a palimpsest created by recycling at least 10 different manuscripts, six of which were in Christian Palestinian Aramaic and four of which were in Greek.

“The Aramaic leaves have been dated to the fifth century through paleographic grounds, and a few leaves were subjected to radiocarbon dating which supported the date. The Greek leaves are from around the sixth century, and once again the date is based on paleography and radiocarbon dating. The manuscript remained in a library of St. Catherine’s (Monastery) until the 19th century, when leaves were sold to European collectors.”

Private collectors Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson, who acquired 138 leaves between 1895 and 1906, donated 137 leaves of the manuscript to Westminster College at Cambridge University, and donated the remaining leaf to the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, Hyland said.

In 2010, the Green Collection of Oklahoma purchased the 137 leaves from Cambridge and donated them to the Museum of the Bible in 2014.

“In 1975, an additional eight folios of the manuscript were found at St. Catherine’s,” Hyland said, “which helps to establish the monastery as the place where the composite was likely created, and where it stayed until the 19th century.”

Hyland elaborated on the work’s historical significance.

“For the first time, a Greek text of Hipparchus’ lost star catalog has been discovered. There were references to the text, but it has not survived,” Hyland said. “The deciphered portion of text discovered on these leaves contains star coordinates for the constellation Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown. The coordinates closely match what the reconstructed position of the constellation was in 129 BC, when Hipparchus was active. The coordinates are more precise than those given by Ptolemy centuries later.

“This is a remarkable insight into the work of an ancient Greek astronomer. Hipparchus likely had access to Babylonian writings on the position of stars and planets. He also likely made his own precise measurements.”

The Ladder of Divine Ascent is on display at the Museum of the Bible and images are viewable online here.

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Diana Chandler is Baptist Press’ senior writer.)