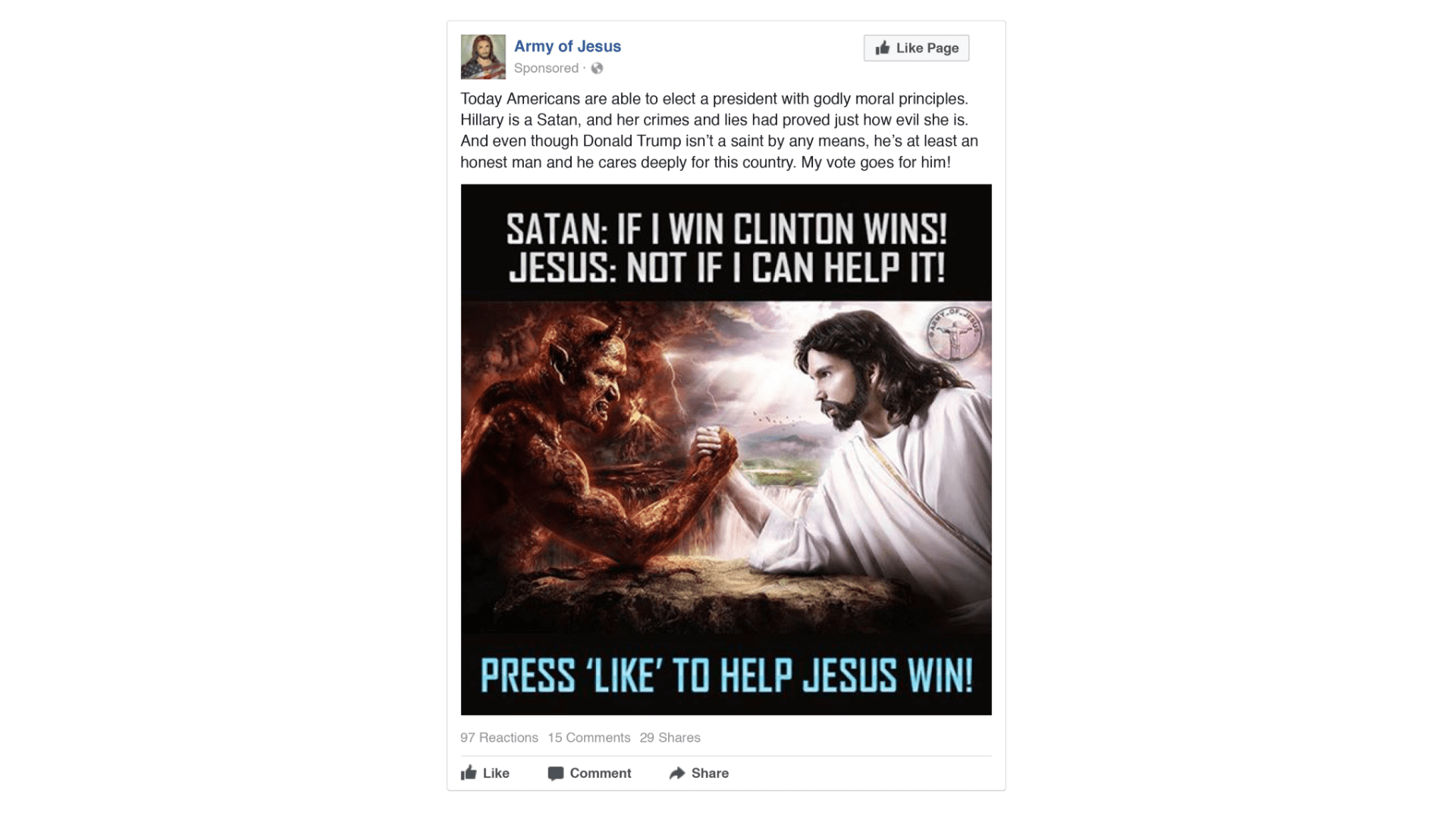

A recent news report about indictments against Russian propagandists for meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election indicated that social media accounts aimed at spreading disinformation (commonly called “trolls”) have been targeting Baptists in attempts to stoke dissension in America.

A company based in St. Petersburg, called Internet Research Agency (IRA), employed and trained workers to flood websites and social media conversations with false and provocative information through fake profiles, groups and paid advertisements on social media, along with inflammatory comments on news articles, while posing as Muslims, African Americans and “middle-class Baptists,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

The posts shared common themes of anger and distrust toward authority, government and news media, said the Journal.

The IRA and other propaganda efforts are allegedly backed by an influential Russian business owner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, who was indicted Feb. 16, along with 12 others, by a federal grand jury as part of an investigation by U.S. Special Prosecutor Robert Mueller.

Many Baptists have witnessed first-hand how vulgar and severe such digital harassment can become.

In recent years, online discussions about events related to the Southern Baptist Convention’s (SBC) annual meeting have triggered activity from what appear to be European ethno-nationalist and American “alt-right” social media profiles.

A Twitter thread for the hashtag #SBC16 was hit with a barrage of offensive messages attacking supporters of a resolution denouncing the use of the Confederate battle flag.

An account with the name “Der Kaiser,” which is German for “the emperor,” hurled crude insults at Alabama resident Debbi Moses on June 15, 2016, after she tweeted messages in support of the resolution.

Der Kaiser’s profile page includes descriptors such as, “trad-Christian,” “traditionalist” and “nationalist,” along with white supremacist slogans in German and hashtags indicating support for the alt-right, former Confederate States of America and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Moses told the Biblical Recorder that most of the language used about her that day on Twitter was too vulgar to repeat, but she said the use of the “N-word” in reference to her grandchildren was “the most hurtful.”

“They saw pictures of me with my grandchildren,” she said, “twins born in Ethiopia and their sister who was born in Guatemala.”

Harassment became so disturbing that Moses almost deleted her Twitter account. She blocked more than 50 accounts that day.

Multiple Southern Baptists told the Recorder they witnessed troll-like activity during the 2017 SBC annual meeting from accounts that were apparently trying to sow discord over a resolution condemning “alt-right white supremacy.”

James Forbis Jr., associate pastor at First Baptist Church in Willow Springs, Mo., said he believes the surge of antagonistic posts exaggerated the appearance of division in the convention.

“I believe that they wanted the world to see an SBC that was severely divided by politics and racism,” Forbis told the Recorder. “By hijacking the hashtag they deceived people into believing they were a part of the SBC and at the meeting.

“There was confusion about what the alt-right is, and there was confusion about what [the resolution on the alt-right] was condemning, and that’s what the trolls latched onto. They took the confusion and ran with it.”

Facebook and Twitter have each shut down millions of fake accounts since 2016, according to news reports.

Online activity by alt-right supporters ranges from intentionally shocking and nonsensical text and images – what Matthew Rose called “moral idiocy” in a First Things article – to sociological and philosophical notions meant to provide white supremacists with a more highbrow public persona.

Some white supremacists who promote “traditionalist” beliefs, which have no apparent connection to Southern Baptist “traditionalists,” are self-described pagans who oppose Christianity, according to Rose, who is director and senior fellow at The Berkeley Institute.

Distinguishing between trolls and active users with extremist ideas can be difficult. Hyper-partisan social media posts on specific political topics that are filled with grammatical mistakes characteristic of non-native English speakers may be helpful clues. Absurd grammar or sentence structure may also indicate that a social media account is automated. These are commonly known as “bots.”

Chris Martin, content strategist and co-creator of LifeWay Social, told the Recorder that social media users should avoid interacting with suspected trolls or bots.

“When you are confronted with trolls, bots, or others attempting to harass you on social media,” he said, “the best course of action is to simply ignore them and move on.”