NEW ORLEANS (BP) – Recent brain research and neuroscience discoveries have pushed to the forefront the questions of what does it mean to be human and do humans have souls.

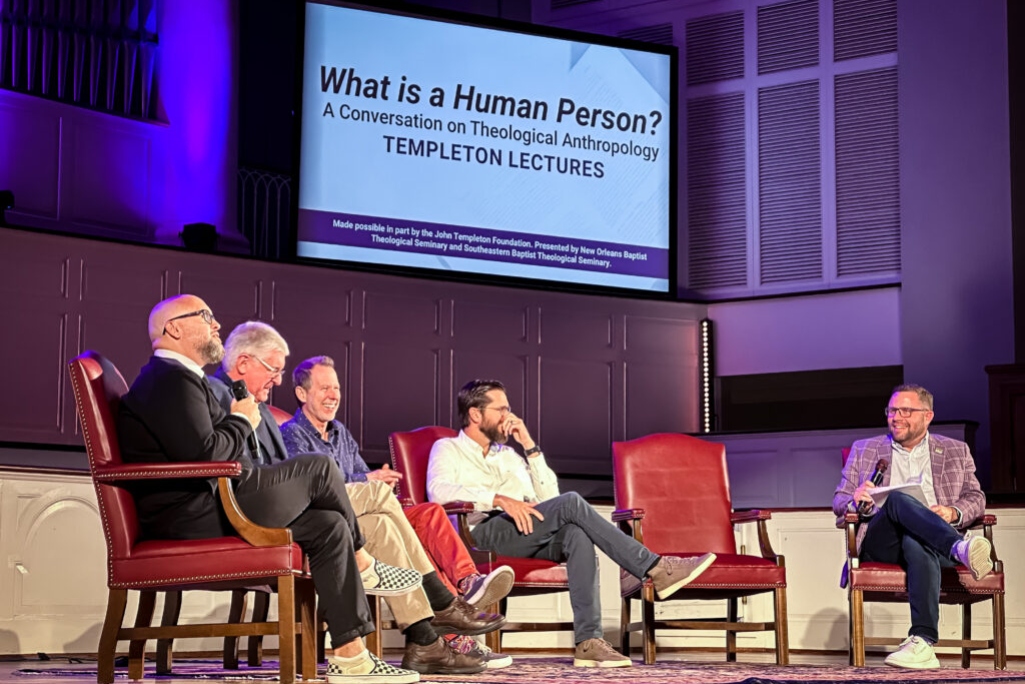

The mind-body question was the focus of the What is a Human Person? A Conversation on Theological Anthropology conference at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, April 28-29. Three perspectives from a Christian viewpoint were presented: substance dualism, physicalism and hylomorphism.

The conference, made possible in part by the John Templeton Foundation and presented by NOBTS and Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, featured Ross Inman, SEBTS professor of philosophy; Stewart Goetz, distinguished professor in philosophy and religion, Ursinus College, Collegeville, Pa.; and Kevin Corcoran, philosophy professor from Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Mich. Each affirmed a belief in a bodily resurrection and in the Christian faith.

Responding to the presentations were Ken Keathley, SEBTS senior professor of theology and director of the L. Russ Bush Center of Faith and Culture; Robert Stewart, NOBTS professor of philosophy and theology and director of the NOBTS apologetics program; and Ian Jones, NOBTS professor of counseling and a licensed professional counselor and licensed marriage and family therapist.

Jamie Dew, NOBTS president, opened the event by noting that the question of human personhood is not new but rather has been debated for 2,500 years. While many varieties of each view exist, the primary approaches are substance dualism, physicalism (or materialism), and hylomorphism, Dew explained.

Dew told of performing 60 funerals during an eight-year pastorate years ago while also watching his preschool-aged children develop cognitively. The issue of life after death and the mind-body question captured his interest and became the subject of his second doctorate, earned from the University of Birmingham, UK.

“Little did I know at that time that the question of human personhood was going to be the bedrock issue that rides under all the cultural issues of today,” Dew said. “How we answer the questions of today in large part comes down to ‘What do you say a human person is?’”

A panel discussion with the speakers followed the evening’s presentations and included Brandon Rickabaugh, assistant professor of philosophy and research scholar of public philosophy, Palm Beach Atlantic University. Rickabaugh’s writings include “The Blackwell Companion to Substance Dualism, Faith and Virtue Formation” and “The Substance of Consciousness: A Comprehensive Contemporary Defense of Substance Dualism.”

Three views

Inman presented the hylomorphic perspective that sees the body and soul as a composite, a union forming a single substance though body and soul have different properties. In this view, the body makes each human an individual; the soul survives death. Inman outlined two biblical parameters: all of Scripture teaches a continued postmortem existence; a future, corporate bodily resurrection will take place when Christ returns.

Goetz, speaking for substance dualism, said this approach has been the “common sensical” view held by humans across cultures and time. Goetz pointed to various neuropsychologists, and others, to show that many today recognize that humans intuitively believe they are more than physical beings. Goetz explained that he sees the human person not as a composite of body and soul, but that the soul is separate and distinct from the body and has “psychological capacities” to think, believe, desire and experience pleasure and pain; and, the soul survives death.

Corcoran’s “constitution view” of a human person is a physicalist or materialist approach that sees human persons as constituted by the physical body, but not identical to the body. Corcoran illustrated his point saying that a copper statue can be hammered down, destroying the statue but leaving the copper itself unchanged. In Corcoran’s view, humans do not have souls but a future bodily resurrection does not require that humans have immaterial souls.

An apologist’s response

Robert Stewart pointed to Acts 17 and said Paul stressed the resurrection before a crowd of Stoic and Epicurean critics because the resurrection is a “non-negotiable part of the Gospel.” Stewart noted that the resurrection is at “the heart of the Gospel” and is included in every sermon recorded in Acts.

“Resurrection also has conceptual difficulties,” Stewart said. “But at the end of the day, Christian apologists can ground their belief in resurrection by appealing to the strong historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus and can say something like, ‘I don’t know how resurrection is possible, but I know that God raised Jesus from the dead, and that shows that resurrection is possible, even if nobody but God understands precisely how it works.’”

Stewart reminded listeners that Scripture is clear that the resurrection, rather than dualism, physicalism, or hylomorphism, is the “defeat of death” and that resurrection is central to the Gospel.

A counselor’s response

Ian Jones stressed the importance of the mind-body question by pointing to 20th century psychologists who ignored the human soul or denied that humans are made in God’s image. While “soul care” was part of 19th century psychology and counseling, a shift occurred with Freud and other voices, Jones said.

“The 20th century saw the fragmentation of human nature and the rejection of the spiritual, particularly in the post-secular personality theories and counseling theories,” Jones said. He added, “Psychology lost its soul.”

Jones stressed that biblical psychology and biblical Christian counseling, regardless of which of the three mind-body approaches is embraced, must begin with God as creator and humans as made in His image. Recent research is supporting a biblical, holistic view of human nature that includes the spiritual as well as physical, Jones noted.

“An eternal perspective in counseling gives meaning and purpose to living,” Jones said. “All problems have a deep and profound spiritual component and all care-giving should respond in terms of both the immediate issue and the eternal consequences.”

A theologian’s response

Ken Keathley noted the widespread disagreement among scholars on how to define a human person and urged listeners to see this moment as an opportunity for “genuine, yet faithful theological development.” Keathley cited author James K. A. Smith in describing this moment as a “Chalcedonian opportunity,” a reference to the early church’s struggle to understand the person of Christ and an example of how the church should respond.

“I believe God has providentially brought us to this moment,” Keathley said. “I do believe God is sovereign and that there’s a reason why He wants us as the church to wrestle with these questions now.”

Believers can approach these questions with confidence knowing that God the Creator is also a revealer of Himself, Keathley said. He added, “Let the conversation continue.”