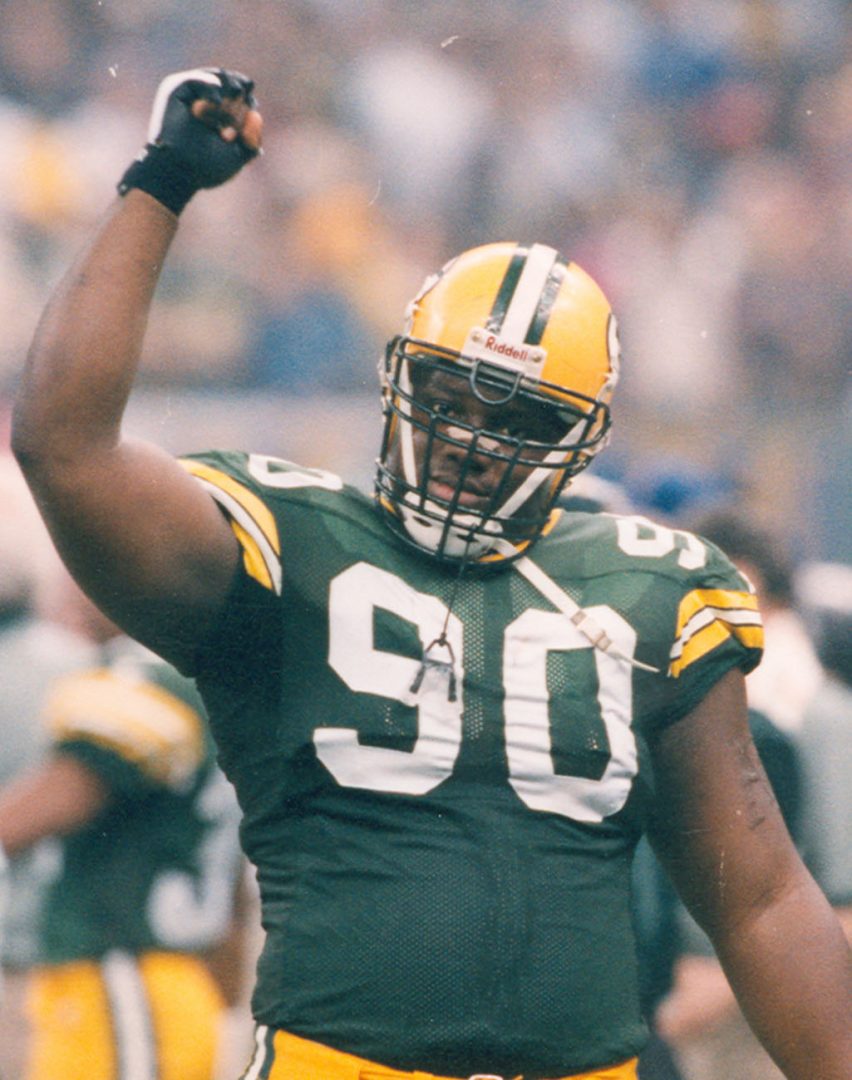

Darius Holland, a defensive tackle with the Green Bay Packers, raises his fist during Super Bowl XXXI against the New England Patriots on Jan. 26, 1997. Final score: Packers 35 - Patriots 21.

FORT BRAGG, N.C. – You would think Jan. 26, 1997, would be the best day of Darius Holland’s life. As a member of the Super Bowl champion Green Bay Packers, he had joined a select fraternity. Holland had just become a world champion.

Holland’s first moments as a Super Bowl winner were everything he had dreamed. All eyes were on him and his teammates. They had the trophy. They felt the confetti fall on their faces. Everywhere they went was a party, and that party would last all night long.

But before Holland headed out on the town to celebrate with his teammates, he had to stop in to check on his family. He had brought them to the Super Bowl, paying for any expense they might have. But when he arrived at their hotel rooms, arguments flared. They fought about what they were going to eat and where they would sleep.

Holland was devastated.

“I went back to my room, sat down on my bed,” Holland said. “And this is what I said, ‘If this is the pinnacle of my life, I’m sunk. I am absolutely sunk. Because this isn’t working.’ I thought that I could outrun my problems. And it was not working.”

Holland wept.

For the next seven years, Holland continued to play professional football. The next year his Packers lost in the first of John Elway’s two Super Bowl wins to finish out his career. Through wins, through losses, through trades – nothing seemed to solve the inner desperation in his soul. At his lowest point, after what Holland believes must have been a period of depression, he turned his life over to Jesus.

More than a quarter century later, Chaplain Captain Holland is now serving another group of men who are coming together for a specific purpose. As an Army chaplain representing Southern Baptists at Fort Bragg, Holland cares for the spiritual needs of soldiers.

Holland grew up on a military installation. His mom was Roman Catholic, and the family went to chapel regularly. When they left the installation, the family attended a local Catholic church, but Holland said he didn’t pay much attention to religion at the time.

Painfully shy and struggling with interpersonal skills, at age 12, Holland grew up fast when his father died. Suddenly, he had to learn to defend himself. Plus, his family had little money. He and his brother shared three pairs of pants and two pairs of shoes. Growing up Black in a New Mexico town that was half white and half Hispanic, Holland was regularly called racial epithets by his own football teammates.

“I learned to hide in plain sight,” Holland said. “But I also learned that in order to get out, I needed an outlet and football allowed that. I remember the day when I went out and played as a freshman or 10th grader. They made me play on junior varsity for one game. I just dominated the kid I was against. My coaches told me I had the football ability to get out of my situation.”

When University of Colorado football coach Bill McCartney, a professing Christian and founder of Promise Keepers, recruited Holland to play football, part of the reason he accepted was because of McCartney’s religious faith. Though not a believer at the time, Holland was looking both to leave home and to find the father figure he didn’t have.

Holland played for some of the greatest collegiate teams of the 1990s at Colorado, concluding with an 11-1 top five finish in 1994. But he still struggled through poverty in college. Drafted in the third round of the 1995 NFL Draft, Holland said he felt more relief than excitement.

“When I got the call, it was like sweet,” Holland said. “I am out. I’m not going to have to live the way I was living. It wasn’t a celebration of accomplishment. It was a celebration of release.”

Money, Super Bowl wins, trades to new locations and even the camaraderie of his teammates couldn’t heal what was broken in Holland. By 2003, life seemed to turn upside down. He hadn’t played much in 2002 as a member of the Minnesota Vikings. He still hadn’t found the peace he had been searching for.

That year he met physical therapist Brett Fischer. It didn’t take long to realize something was different about Fischer’s life. He had joy that Holland longed for. Fischer introduced him to his pastor, who flew to Denver (where Holland was playing in 2003) weekly to disciple him.

One day, when he was driving home, everything began to fall into place.

“I just started pouring out lots of water, crying like a baby,” Holland said.

God showed him that the pain in his life wasn’t a result of his mom, his dad, or anyone else in his life. It was his sin.

“Lord, OK, I see it. I get it. I understand,” Holland said. “But if you’re going to do this, you can’t let me ever go back. I can’t. It would crush me if I ever had to go back [to the life I had]. So, I’ll do whatever you want.”

Holland’s career came to an end shortly after that. He left a million dollars on the table because he no longer needed football to run away from his past. He was ready to move on.

Though he is a strong introvert, God would in time call him into ministry. He pastored True Life Church in Thornton, Colo., for more than a decade. In 2015, he graduated from Gateway Seminary with a Master of Theological Studies and earned a doctorate from Gateway a few years later.

A friend told him he’d make a good chaplain, but Holland figured he was too old and broken by that time to go into the military. Yet when he read Nik Ripken’s book The Insanity of God, the Lord challenged him with a probing question: “How far are you willing to go for the gospel?” God brought chaplaincy to mind.

Holland had spent a lot of his early life running. He wouldn’t run from God’s call again. For several years, he served as both a pastor at True Life and a chaplain with the National Guard. Then, in 2020, God called him to North Carolina to serve at Fort Bragg.

Holland said his job is to provide advice from a faith perspective and help soldiers get what they need to celebrate their faith. He also advises leaders on issues of religion and morale in the context of their unit.

“You are spending your time trying to set up a hedge of protection for the people whom God has put into your care,” Holland said. “So when they walk in with a frame of mind that is dealing with a difficult situation, you can reframe it according to the Bible so that when they walk away, they can be different.”

Holland is grateful for how Southern Baptists have equipped him for that role.

“What really has allowed me to walk in and actually do my job is the fact that I’ve been trained, equipped and supported to accomplish that task,” Holland said. “So, if I were speaking to the reader right now, I would say, ‘It’s because of your commitment in NAMB and in some ways in the IMB that is allowing someone like me to get trained, equipped, sent and supported, so I can do this ministry.’”

For more information about Southern Baptist chaplaincy, visit namb.net/chaplaincy.

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Tobin Perry is a freelance writer with more than 20 years of writing experience with Southern Baptist organizations. He can be reached at TobinPerry.com. This article originally appeared in the January 2023 issue of the Biblical Recorder magazine.)