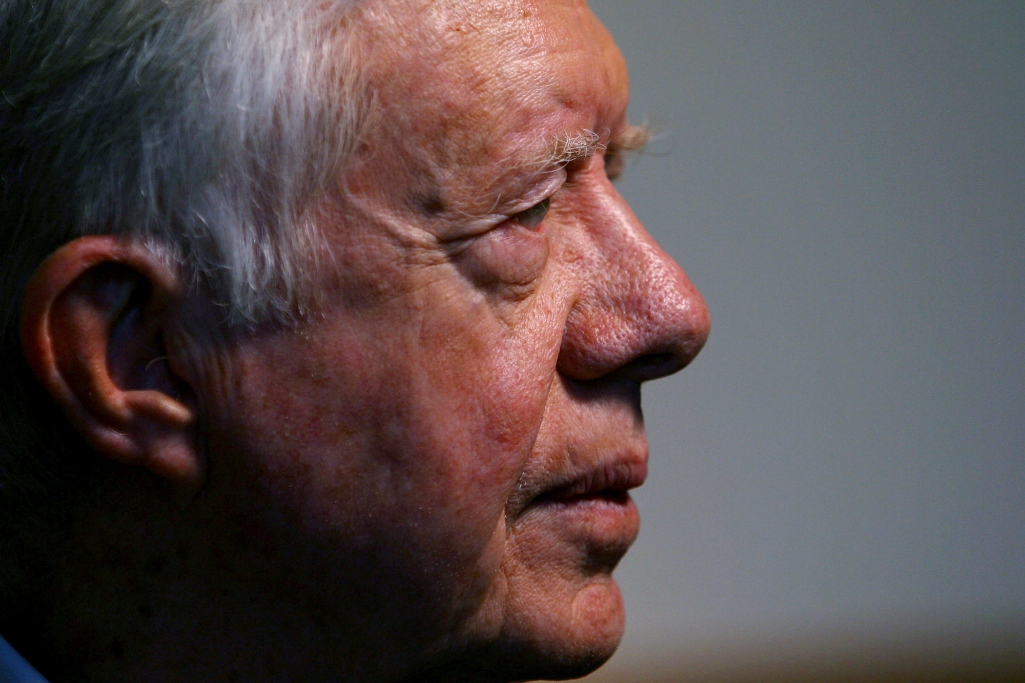

Former President and Nobel Peace laureate Jimmy Carter speaks to the Associated Press in Copenhagen, Denmark, Dec. 13, 2002.

The world received the news this week that James Earl Carter Jr., the 39th president of the United States, had died at the age of 100.

Almost immediately tributes started pouring in to give thanks for the former president’s life of humility and service. Likewise, dozens and dozens of stories were posted to recount and evaluate the presidency of Jimmy Carter, who had traveled from the U.S. Navy to the work of a peanut farmer to Georgia governor to the White House, most noting that he was quite effective as a former president while his four years as president were evaluated less favorably.

Almost everyone agrees that the highwater mark of those years, in addition to his desire to bring personal virtue and decency to the White House, were the resilient efforts to bring about the Arab-Israeli peace accord in 1978 as Carter brought together Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. For these and similar efforts, Mr. Carter was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

Regardless of whether one identifies as Democrat, Republican or Independent, it seems that Jimmy Carter was deeply admired as a person. Over the past four decades, according to the annual Gallup Poll, only Billy Graham and Ronald Reagan ranked higher than Carter on the most admired list. In these various Gallup Polls, personal admiration for Carter consistently and significantly exceeds the numbers evaluating his years as president. His 1980 campaign for a second term ended with a sound defeat to Ronald Reagan.

As a former president following his time in office, he labored tirelessly as a mediator, seeking to bring peace to areas of conflict in the world, which at times seemed to bring him into conflict with U.S. foreign policy. He and the team at the Carter Center, which was established in Atlanta, Georgia, following his presidency, worked strategically to eliminate guinea worm disease, river blindness and other diseases in majority world contexts. He also sought to ensure the integrity of elections in developing democracies worldwide. In the United States, he and his wife, Rosalynn, who died in 2023, gave freely of their time to help build hundreds of houses with Habitat for Humanity. The Carters enjoyed 77 years of exemplary and faithful marriage commitments.

All along, Mr. Carter continued to teach Sunday school and to talk freely about his faith in Jesus Christ and his born-again experience — just as he did on the campaign trail when running for the presidency in 1975-76 and when he gave his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. Mr. Carter’s candidacy in 1976 had been greatly helped by millions of Southern Baptists who supported him because of his identification as a loyal Baptist lay leader, even though most sociologists are quick to note that he did not win the overall evangelical vote in either 1976 or 1980.

Jimmy Allen, pastor of the influential First Baptist Church, San Antonio, Texas, and president of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) from 1977 to 1979, had led the efforts to rally support for the Carter-Mondale ticket not only from Baptists but from others who could identify with Carter’s faith commitments. Others, far more competent and insightful than me, including presidential historians and political scientists, can evaluate the one-term Carter presidency.

Today, my purpose is merely to offer a few brief reflections on my personal encounters with the former president. In 1998, I was invited to visit with Mr. Carter at his home in Plains, Georgia. The invitation came as he placed a call to my office at Union University. I will never forget my assistant walking into my office and saying there was someone on the phone who said he was Jimmy Carter, and it sounded just like him. Having never met the former president, I picked up the phone and enjoyed a pleasant conversation.

He told me that he had read my book, “Christian Scripture” (B&H, 1995), and wanted to discuss further matters of biblical inerrancy, authority and interpretation. Southern Baptist leaders Jim Henry, Morris Chapman, Jimmy Draper, Tom Elliff, Paige Patterson, Timothy George and a few others were also invited to the time of lunch and conversation. I was certainly surprised by the invitation but was quick to accept. Mr. Carter had asked Timothy George and me to join him in his study to discuss his understanding of biblical authority and the priesthood of the believer, and other Baptist distinctives, prior to lunch with the others in his home.

Mr. Carter wanted to be a peacemaker (Matthew 5:9) in the world and desired to be a peacemaker in the Southern Baptist Convention. Everything about the day and the visit with him was amicable, even as the conversations were frank and substantive. The former president, who as a polymath, was seemingly interested in almost everything, including matters of theology and denominational life, noted that although he had been largely influenced by the writings of European theologians, he affirmed the authority of Scripture. His laudable kindness, humility and his desire to understand areas of agreement and disagreement continue to stand out in my memory.

The 39th president fully engaged in a wide-ranging conversation, noting that he personally supported the sanctity of life, even though he said as president he had sworn to uphold the laws of the land, including the 1973 Supreme Court decision on abortion. He differed with Timothy George, who wanted to help him understand the difference between “the priesthood of believers” and the individualized and privatized view of “the priesthood of the believer.”

Mr. Carter expressed his deep commitments to racial reconciliation and religious liberty, stressing his opposition to religious persecution. He was humble, eager to listen and learn, and hopeful to bring together moderates and conservatives in the SBC, while observing that he had more closely identified with moderates. In March 1998, all who attended the meeting at the Carter’s home in Plains agreed to sign a document of cooperation with a diverse group of Baptists from various Baptist affiliations. The declaration included strong statements related to racial reconciliation and religious persecution.

Shortly thereafter, I again received an invitation from the former president as he wanted a small group of representative leaders from predominantly white Christian colleges and universities across the country to meet at the Carter Center in Atlanta with leaders of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). The conversations involved ways for our institutions to work together toward racial reconciliation while advancing matters of agreement about distinctive approaches to higher education. The conversations were warm, winsome, helpful and instructive, encouraging us toward greater cooperation and collaboration when and where possible.

It has certainly been memorable to reflect on both of these events in light of the death of the 39th president earlier this week.

While I have often found myself in disagreement with Mr. Carter on matters regarding public policy, theology and ethics, I am nevertheless quite grateful to God for these personal opportunities to observe and learn from the former president, seeing firsthand Mr. Carter’s intention and desire to live out his faith as a follower of the Lord Jesus Christ.