(EDITOR’S NOTE – This article is the first in a series of articles on Black Baptist leaders in the history of North Carolina Baptists.)

Black History Month is an opportune time to be reminded of the inspiring life and ministry of John Day, Jr. (1797-1859), one of the most significant Black Baptists of North Carolina. Among his most noteworthy accomplishments is the fact that he was one of the first missionaries to be supported by the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), and that he served as the superintendent of missions for Liberia – the only field of missions for Southern Baptists at the time other than China.

Day was born free in Greensville County, Va., in 1797, but moved with his father and brother to Warrenton, N.C., in 1817. Day’s father, John, Sr., allegedly had been given up at birth by his white mother and black father and was raised in a Quaker community.

John, Sr. became a skilled and noted cabinetmaker whose second son, Thomas, not only adopted the same vocation, but surpassed his father in being recognized as a renowned master furniture maker.

In 1820, three years after the Days arrived in Warrenton, John, Jr. was baptized by a Baptist preacher in Warren County. Two years later, Day went to study under Abner Clopton, the pastor of the Baptist church in Milton, N.C., and the superintendent of the Milton Female Academy. Day supported himself and his family – he married in 1822 – by crafting furniture, like his father and brother.

However, his greatest desire was to be a missionary.

Day’s first attempt to be appointed as a missionary failed when, as Day claimed, his application to be appointed by the Triennial Convention, the first national Baptist organization in America (founded in 1814) was rejected in 1824 because of his Arminian theology.

By saving money, raising support and selling all his goods, Day was able to move his wife and four children in 1830 to Liberia, Africa, to serve as a missionary in that colony. Liberia had been established a decade earlier by the American Colonization Society in their effort to send blacks back to Africa.

Within months of arriving in Liberia, Day tragically lost his entire family to disease. But he remained in the colony, serving as a preacher, teacher, missionary and, at times, political leader.

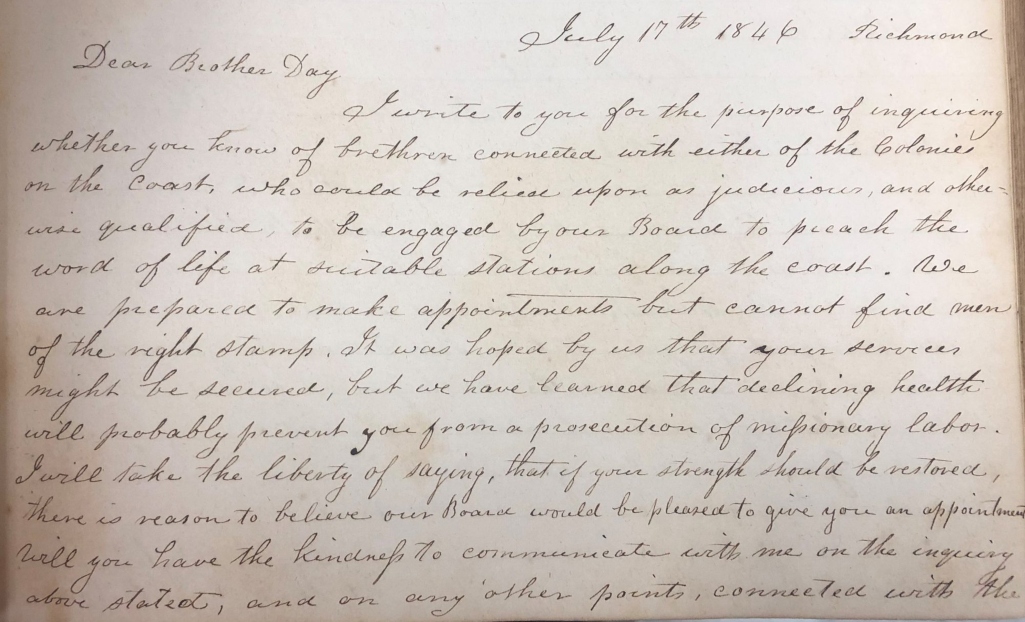

In 1835 the American Baptist Missionary Union – the successor to the Triennial Convention – began supporting him as a missionary. He resigned in 1844, criticizing the Union for not adequately financing his endeavors.

Two years later, however, he accepted an appointment from the Foreign Mission Board of the newly formed SBC.

For the next 13 years Day served as the SBC’s superintendent of missions in Liberia. As such, he hired, fired and directed missionaries and other personnel, and controlled the allocation of funds for SBC missions in Liberia. In contrast, the American Baptist Missionary Union used white missionaries to oversee their Liberian mission, which ended in 1856.

Before his death in 1859, Day pastored Providence Baptist Church in Monrovia, Liberia, established a school for high school aged boys, helped to write Liberia’s Declaration of Independence (1847) and served as both the country’s vice president and later as its chief justice.

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Brent J. Aucoin is professor of history and associate dean of the college for academic affairs at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wake Forest, N.C.)