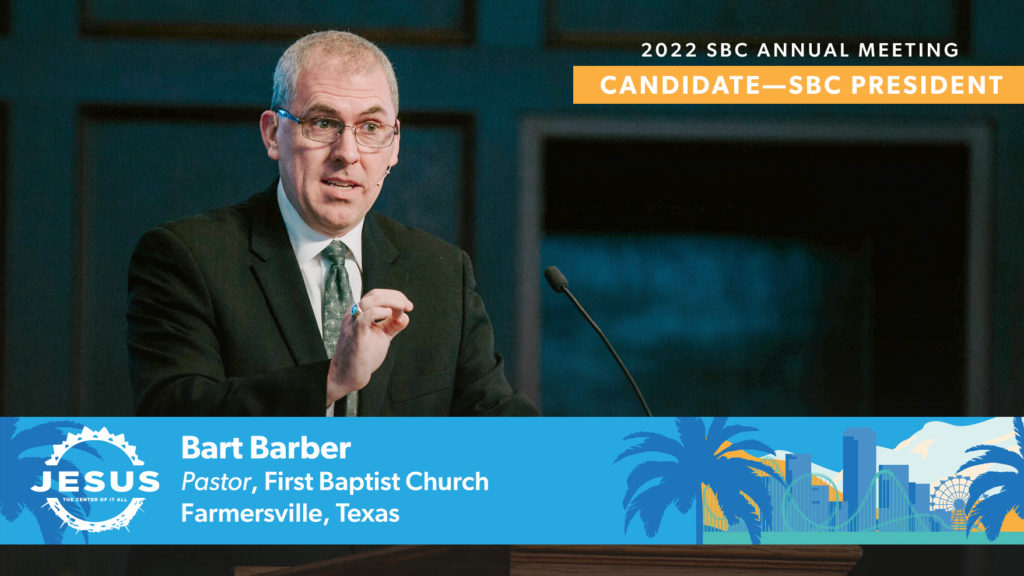

EDITOR’S NOTE – This essay from Bart Barber is published in conjunction with essays from Tom Ascol and Robin Hadaway. Ascol, Barber and Hadaway are the three known candidates to be nominated for Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) president at the 2022 SBC annual meeting in Anaheim, Calif.

Today I was reading from the Second London Confession the following passage from Chapter XXVI, Section 15:

In cases of difficulties or differences, either in point of Doctrine, or Administration; wherein either the Churches, in general, are concerned, or any one Church in their peace, union and edification; or any member, or members, of any Church are injured, in or by any proceedings in censures not agreeable to truth, and order: it is, according to the mind of Christ, that many Churches holding communion together, do by their messengers meet to consider, and give their advice in, or about that matter in difference, to be reported to all the Churches concerned; howbeit these messengers assembled, are not entrusted with any Church-power properly so called; or with any jurisdiction over the Churches themselves, to exercise any censures either over any Churches, or Persons: or to impose their determination on the Churches, or Officers.

More than 340 years ago, the Particular Baptists explained the autonomy of the local church in a manner almost perfectly tailored to the challenges of the present day.

Consider the following points.

First, associations and conventions of churches do not have “Church-power”—are not authorized to act as though they were churches. The SBC does not admit or dismiss individual believers to and from membership. It does not set apart pastors or deacons. It does not baptize anyone or conduct any observance of the Lord’s Supper. It cannot do what is reserved to churches to do.

Second, associations and conventions of churches do not have jurisdiction or power over churches or church members. They cannot undo even the most insignificant action of the least attended business meeting of the smallest cooperating church. They cannot confiscate their land or defrock their pastors.

These truths are the core realities of local church autonomy, and they are not conferred upon our churches by the convention. We have local church autonomy, not by the Southern Baptist Convention’s magnanimity, but rather by its inability. There’s no vote the convention could take and no mistake it could make that would compromise local church autonomy, because it simply lacks the legal standing to take over your church’s staff, budget, property and name.

But note carefully what local church autonomy does not prevent.

It does not prevent gatherings of churches like the SBC from identifying and discussing problems in local churches. These may be doctrinal problems, such as when churches disregard the limitation of the office of pastor to men.

These may be problems of “administration,” such as when churches choose to cover up abuse or knowingly hire abusers. It does not violate any church’s autonomy for sister churches to say, “We think you have a problem in your church.”

It does not prevent the convention from addressing occasions when members have been “injured” by a church’s actions. If the convention should choose, when members of our churches reach out to us seeking help because of spiritual or physical injuries that they have sustained, to ignore those cries for help, we have chosen to be obtuse for reasons other than our distinctive belief in local church autonomy.

It does not prevent the convention from “giving their advice” about disruptive matters in local churches. Indeed, the article explicitly suggests that advice on such matters should be distributed abroad to all the churches for their benefit. By doing so, groups like the SBC can help to fulfill the “as in all the churches” level of accountability that appears in passages like 1 Corinthians 14:33.

It does not prevent the convention from disfellowshipping wayward churches when they reject the core doctrinal and administrative judgments of the broader community of churches. The convention has no power to accomplish the excommunication of any member from his local church (the “censure” mentioned in the article), but it does have the right to determine the extent to which the churches are “holding communion together” on the basis of faith and practice.

Key misunderstandings of the doctrine of local church autonomy have played a role in the mishandling of reports of sexual abuse at the SBC Executive Committee. Some of the same misunderstandings were used to object to the Conservative Resurgence on the ground that it violated local church autonomy. As we implement necessary reforms in response to the Sexual Abuse Task Force report, we as a convention will need to understand which proposed actions respect the autonomy of the local churches and which actions would fail because of that autonomy. To succeed at that task, we would all do well to look back at this historic statement of faith and to refresh our memories about what local church autonomy is and is not.

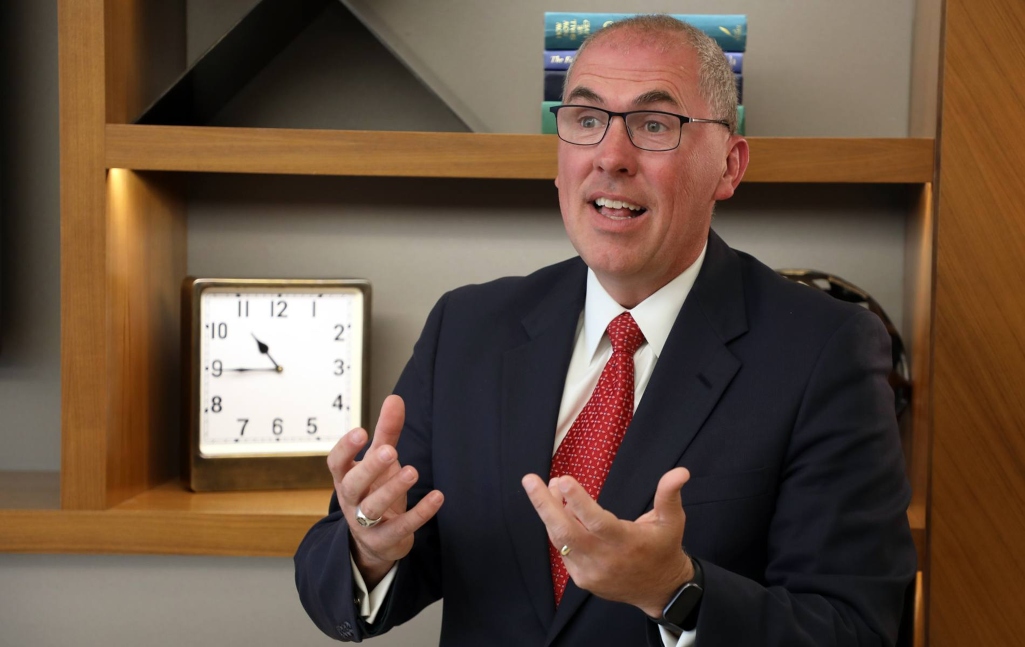

(EDITOR’S NOTE – Bart Barber is senior pastor of FBC Farmersville, Texas.)